Class 8 students study in the computer lab at Marble Quarry Primary School in Kajiado Central on the outskirts of Nairobi, Kenya.

Credit: GPE/Luis Tato

The cost of achieving the national SDG 4 targets that low- and lower-middle-income countries have set for themselves is beyond reach: an annual financing gap of USD 97 billion would need to be covered in 2023–30.

The cost of digital transformation in education is an additional cost on top of that, which is estimated in the new 2023 GEM Report on technology in education released this week. Any discussion about investments now for a future transformation must be clear from the get-go about the finances required to sustain the change.

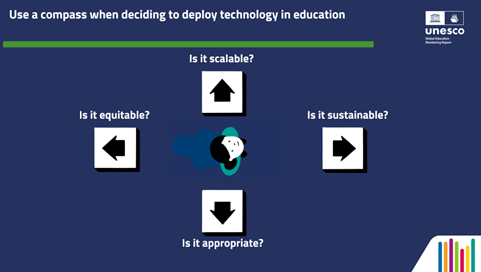

The 2023 GEM Report argues that the adoption of education technology cannot follow a blanket approach. It must be implemented on countries’ own terms, appropriate to their contexts, compatible with equity and inclusion objectives, commensurate to scaling potential and mindful of long-term adverse economic, social and environmental consequences.

The report looks at three scenarios of increasing ambition for digital transformation to which countries might aspire:

- A basic offline scenario where there is some digital teaching and learning opportunities and some shared devices, but no internet.

- A fully connected schools scenario with more devices available.

- A fully connected schools and homes scenario with electricity and devices, not unlike what the world’s richest countries experienced during COVID-19 with digital learning.

Such a transformation entails major costs. Preparing systems for digital learning involves content development, teacher training, student and family engagement, capacity for data use at national and school level, and capacity for policy development.

For instance, teachers will need to be trained, both initially and on an ongoing basis, while schools will need to be equipped with capacities for managing and using data.

On top of that, devices need to be distributed, and replaced every five years or so, and internet connectivity. One-off cost assumptions to connect an average school (USD 15,000) were based on the Giga project, excluding some of the most remote schools, which it would take millions of dollars to connect.

Universal connection was assumed to be equivalent to 90% of the International Telecommunication Union (ITU) estimate for all those age 10 and older to 4G or the equivalent, including mobile infrastructure, fiber, network operations, remote area coverage, policy and additional digital skill training.

On top of these costs, it is necessary to add the operational cost of paying for data consumption both at school (for both scenarios) and at home. The home-based scenario is predicated on the Alliance for Affordable Internet estimate that the cost of 1 GB of mobile broadband should be no more than 2.45% of monthly income to meet the affordability criterion in low- and lower-middle-income countries. Chapter 22 of the 2023 GEM Report lists all these items individually with assumed costs for each.

Many of the assumptions made in these estimates are difficult to specify with precision: it depends on how targets are defined, on the price level at the time the estimate is made, and on the reference period considered.

In the case of internet connectivity, for example, the UN estimated that the cost of connecting the remaining 3 billion people to the internet by 2030 would be USD 428 billion, while a consulting firm estimated a figure five times as high – or USD 2.1 trillion.

Still, there is no doubt that the sums required are substantial. Of course, the cost of digital transformation need not exclusively be a burden on the education ministries’ budget; some of the costs may even be borne by non-state actors, for instance, investments in connection to the internet. Either way, the costs of country choices need to be clear before making plans.

Adding up these costs, the third option with digital learning at home by 2030 is out of reach for low- and lower-middle-income countries. That scenario would cost around USD 1 trillion in capital expenditure, but almost USD $1 billion every day after that simply to maintain.

The 2023 GEM Report has therefore focused on a combination of the two first scenarios: low-income countries achieve the first, basic offline scenario, while lower-middle-income countries work towards the second, fully connected schools scenario.

The 2023 GEM Report has therefore focused on a combination of the two first scenarios: low-income countries achieve the first, basic offline scenario, while lower-middle-income countries work towards the second, fully connected schools scenario.

This would cost these countries USD 21 billion per year until 2030 on capital expenditure and USD 12 billion per year on maintenance. When added to the financing gap, which low- and lower-middle-income countries are already facing to reach their national SDG 4 benchmarks, this would increase their financing gap by 50%.

The conditions are not yet in place for expenditure on technology to substitute any of the current expenditure. In the short to medium term, in order to be acceptable, any such investment in technology would have to be additional to other desperately needed investments, such as making classrooms conducive to learning, filling teacher gaps and ensuring every student has a textbook.

Policy makers need to think extremely carefully before committing to costs that might widen the inequality gap and generate additional barriers to equal learning opportunities for disadvantaged populations.

As the new report states, there is at present a distinct lack of rigorous, impartial evidence on technology in education. Therefore decisions are not always made wisely. Two studies in the United States estimated that 67% of education software licenses purchased were unused, for example.

The emphasis on digital transformation in conversations around the world is weighing heavily on these decisions. Digital learning featured as one of the five thematic action tracks at the Transforming Education Summit in September 2022, partly as a result of the focus on technology during the COVID-19 pandemic.

At a national level, governments do not want to be excluded from the changes that new technologies are bringing to economies and societies; many believe they can leapfrog some of the challenges that have marred their development in the past.

Understanding the cost implications of bringing forward digital transformation in education – as well as which elements are transformative – is a key policy issue.

The 2023 GEM Report calls for policy makers to make sure that their uses of technology in education are scalable: that decisions are made only when there is sufficient evidence of their costs and benefits for all.

Source: The cost of digital transformation is well beyond poor countries’ reach | Globalpartnerships.org